Tips to Help General Aviation Pilots Improve Overwater Flight Planning

A General Aviation Joint Safety Committee (GAJSC) study (PDF download) suggests that improved survival planning and training are key factors in increasing pilot survivability in accidents and incidents. Earlier this year, we looked at some basic survival skills and resources. Let’s now take a closer look at some safety tips for overwater operations.

While overwater operations might initially conjure up long-distance trans-oceanic flights outside the domain of most GA flying, there are many places in the US where a forced landing could require us to swim to survive. That means we should know the principles of a successful water landing (ditching), and be equipped with and know how to properly use the appropriate survival gear.

Preflight Planning

When we think of lakes in the United States, the five Great Lakes on the northern tier and the Great Salt Lake in Utah come to mind. Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world, is roughly the size of South Carolina. But there are hundreds of lakes and rivers where, depending on your course and altitude, ditching might be your best or only option. That’s why pilots should plan their route to avoid or minimize their time over water and be equipped for survival and rescue if ditching is necessary.

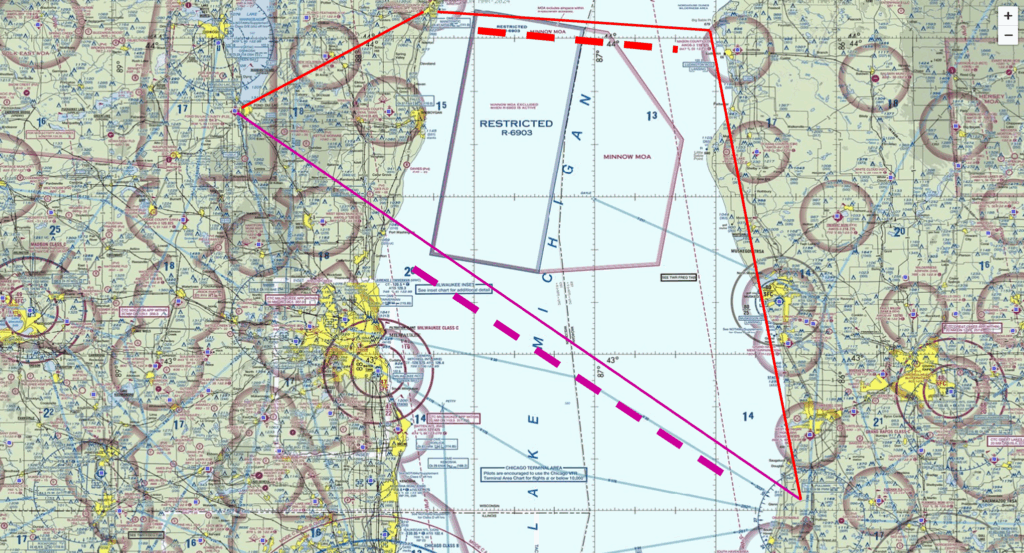

Here’s an example:

Let’s say we’re on the way to Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, traveling northwest at 6,500 feet in a Cessna 172. The direct route involves an 88 nautical-mile overwater segment (magenta line). Lake Michigan’s mean surface elevation is 575 feet mean sea level (MSL), so in this example, figure we’ll be about 6,000 feet above the water. With power off, we can glide approximately 1.5 miles per thousand feet of altitude above the surface. This means there will be about 70 miles where we can’t glide to shore if the engine fails (dashed magenta line).

We could go further north for a narrower crossing (red line), but we’d still have a 30-mile open water leg (dashed red line), and the trip would be 60 miles longer. Whichever route we choose, the higher we can cruise, the better. Altitude will give you more time to deal with emergencies, improve communications, and reduce the time you’re beyond gliding distance from shore. You may not be required to equip with flotation, signaling, and survival gear, but for trips like this, it makes sense. More on that later.

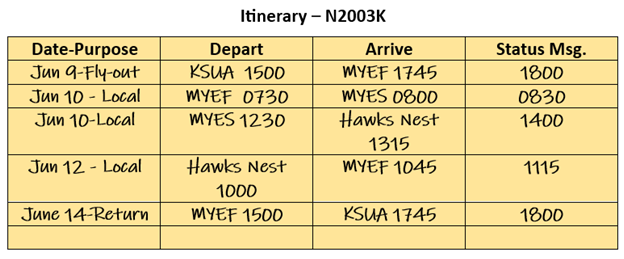

You’ll want to file a flight plan for any overwater flight, and requesting flight following makes sense too. But if you’re going on a multi-day trip to areas where communication may be a challenge, you may also want to file an itinerary with a trusted agent or friend before you leave. If you’re equipped with a satellite phone, or even a satellite messaging device, you can transmit periodic status reports to your agent.

Regulation Review

Once you can no longer see land, one body of water looks like any other, so pilotage won’t work. Likewise, VOR, ADF, and VHF communications may not be available. That’s why 14 CFR section 91.511 specifies communication and navigation equipment required when operating more than 30-minutes flying time or 100 nautical miles from the nearest shore. Depending on where you’re flying, that means you may have to equip with at least one high-frequency radio.

Additionally, the emergency equipment requirements in 14 CFR section 91.509 are a good guide for any overwater operations beyond gliding distance to shore.

Review Your Equipment Needs

When it comes to emergency equipment, the most immediate water survival need will be something to keep you afloat. Personal flotation devices (PFDs) are a good idea to have onboard during extended overwater flights. Many inflatable PFDs are wearable, relatively compact, and won’t significantly restrict your movement or impede egress from the aircraft – providing you don’t inflate before exiting. Consider models with pockets for essential personal survival gear. Many overwater pilots wear vests that contain essential survival equipment under their PFD. That way they’re at least equipped with the basics to survive the first few hours at sea.

Adding a life raft to the mix can be expensive and heavy, but it can help greatly extend survival time from minutes or hours to days or weeks.

If you make frequent trips overwater or to the back country, it might make sense to own and maintain additional survival equipment to supplement what you carry on every flight. If you only occasionally make overwater trips, renting equipment is a good option. Many sources of rental survival gear are located on the coasts and are convenient to airports.

Water Landing Prep

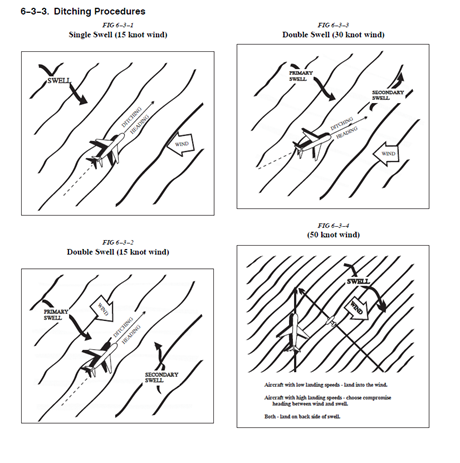

Making a good water landing — ditching — is an essential step to water survival. Pilots should review ditching procedures in the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) Chapter 6, Section 3 (6-3-3) before conducting overwater operations. Having these procedures fresh in your mind will help increase your chances of a successful water landing.

How much can be accomplished before ditching is directly proportional to how high we’ve been cruising and how much power is available.

Here are a few safety items to consider before a water landing:

- Fly the aircraft at best glide speed

- Use power (if available) to control sink rate & extend glide

- Use a soft-field landing technique

- Gear up if retractable – door(s) unlatched

- Aim for any vessels you see

- Transponder to 7700

- Mayday call – state position and persons on board

- Get raft ready – if accessible

- Tighten PFDs and restraints

- Passengers to brace position

After a Water Landing

Once on the water, you’ll want to exit the aircraft quickly. Successful egress is more likely if you have good muscle memory as to the door latch location and operation, emergency exits, and restraint systems. Crew or passengers closest to doors must exit first.

Water egress training, available from various institutions and vendors, is highly recommended for pilots and passengers alike. The FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute offers GA survival courses, including ditching/sea survival and underwater egress. See Basic Survival Training | Federal Aviation Administration.

Another emergency equipment item to consider that can help after ditching is an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon or EPIRB. You can think of EPIRB as a marine ELT. They’re waterproof and they transmit information on 121.5 and 406 MHz emergency frequencies to alert the authorities to your situation via satellite and pinpoint your position.

Once you’re floating in the water, your next most urgent task will be to get out before you become too cold to function. The chart helps explain why and gives us an idea of how long we might be able to survive immersion.

Keep in mind that while most overwater GA flights are successful, it’s good to be prepared for when things don’t go as planned. Hopefully these tips will help better prepare you for an emergency water landing should the situation ever arise.